Originally posted on KrebsOnSecurity on April 9, 2018.

Social media sites are littered with seemingly innocuous little quizzes, games and surveys urging people to reminisce about specific topics, such as “What was your first job,” or “What was your first car?” The problem with participating in these informal surveys is that in doing so you may be inadvertently giving away the answers to “secret questions” that can be used to unlock access to a host of your online identities and accounts.

I’m willing to bet that a good percentage of regular readers here would never respond — honestly or otherwise — to such questionnaires (except perhaps to chide others for responding). But I thought it was worth mentioning because certain social networks — particularly Facebook — seem positively overrun with these data-harvesting schemes. What’s more, I’m constantly asking friends and family members to stop participating in these quizzes and to stop urging their contacts to do the same.

On the surface, these simple questions may be little more than an attempt at online engagement by otherwise well-meaning companies and individuals. Nevertheless, your answers to these questions may live in perpetuity online, giving identity thieves and scammers ample ammunition to start gaining backdoor access to your various online accounts.

Consider, for example, the following quiz posted to Facebook by San Benito Tire Pros, a tire and auto repair shop in California. It asks Facebook users, “What car did you learn to drive stick shift on?”

I hope this is painfully obvious, but for many people the answer will be the same as to the question, “What was the make and model of your first car?”, which is one of several “secret questions” most commonly used by banks and other companies to let customers reset their passwords or gain access to the account without knowing the password.

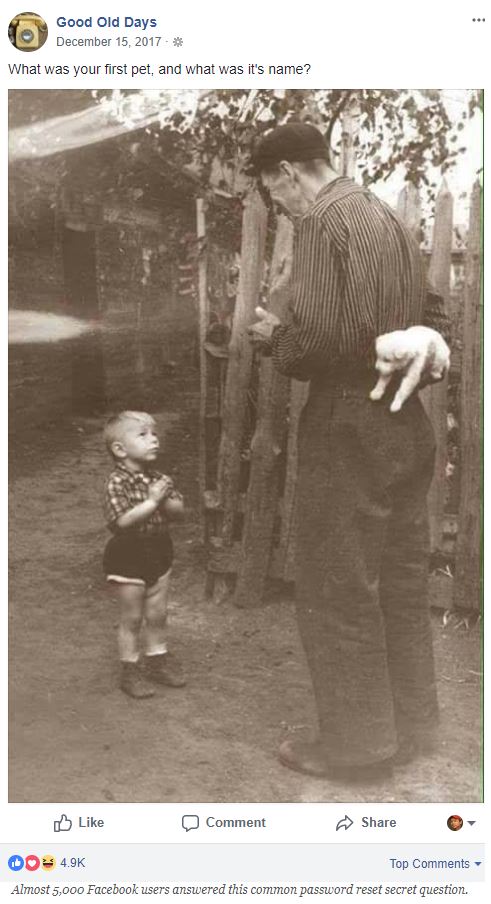

Probably the most well-known and common secret question, “what was the name of your first pet,” comes up in a number of Facebook quizzes that, incredibly, thousands of people answer willingly and (apparently) truthfully. When I saw this one I was reminded of this hilarious 2007 Daily Show interview wherein Jon Stewart has Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates on and tries to slyly ask him the name of his first pet.

Womenworking.com asked a variation on this same question of their huge Facebook following and received an impressive number of responses:

Here’s a great one from springchicken.co.uk, an e-commerce site in the United Kingdom. It asks users to publicly state the answer to yet another common secret question: “What street did you grow up on?”

This question, from the Facebook account of Rving.how — a site for owners of recreational vehicles — asks: “What was your first job?” How the answer to this question might possibly relate to RV camping is beyond me, but that didn’t stop people from responding.

The question, “What was your high school mascot” is another common secret question, and yet you can find this one floating around lots of Facebook profiles:

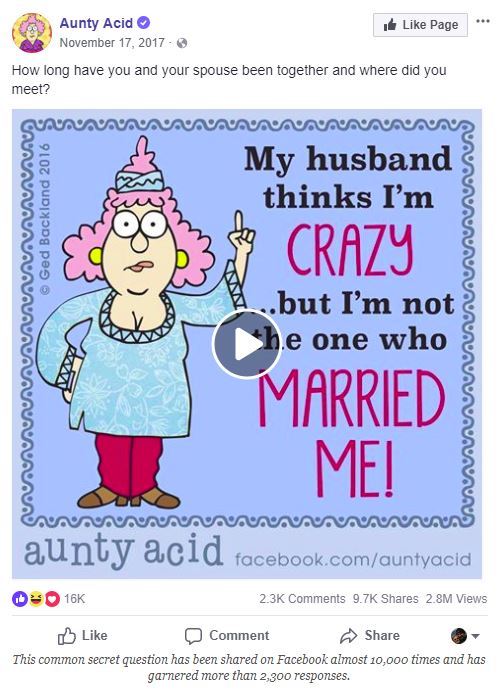

Among the most common secret questions is, “Where did you meet your spouse or partner?” Loads of people like to share this information online as well, it seems:

Here’s another gem from the Womenworking Facebook page. Who hasn’t had to use the next secret question at some point? Answering this truthfully — in a Facebook quiz or on your profile somewhere — is a bad idea.

Do you remember your first grade teacher’s name? Don’t worry, if you forget it after answering this question, Facebook will remember it for you:

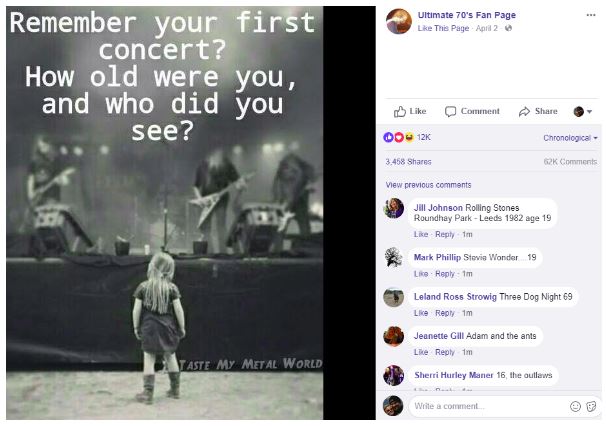

I’ve never seen a “what was the first concert you ever saw” secret question, but it is unique as secret questions go and I wouldn’t be surprised if some companies use this one. “What is your favorite band?” is definitely a common secret question, however:

Giving away information about yourself, your likes and preferences, etc., can lead to all kinds of unexpected consequences. This practice may even help turn the tide of elections. Just take the ongoing scandal involving Cambridge Analytica, which reportedly collected data on more than 50 million Facebook users without their consent and then used this information to build behavioral models to target potential voters in various political campaigns.

I hope readers don’t interpret this story as KrebsOnSecurity endorsing secret questions as a valid form of authentication. In fact, I have railed against this practice for years, precisely because the answers often are so easily found using online services and social media profiles.

But if you must patronize a company or service that forces you to select secret questions, I think it’s a really good idea not to answer them truthfully. Just make sure you have a method for remembering your phony answer, in case you forget the lie somewhere down the road.